Redesigning Work for AI Era Success

I hope you're doing well. Many of you in our profession may know the Hackman and Oldham Job Characteristics Model.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, organizations aggressively optimized work to improve efficiency. Large employers such as AT&T, General Electric, airlines, and other complex operations broke jobs into narrowly defined tasks. While productivity often improved on paper, engagement, responsibility, and pride in work eroded.

Managers blamed incentives or attitudes, but the deeper issue was structural. J. Richard Hackman, trained at Yale and later a professor at Harvard, observed inside these organizations that people disengaged not because they lacked motivation, but because job design stripped away ownership, discretion, and visibility into outcomes. Greg Oldham, working closely with Hackman in the early to mid-1970s, brought empirical rigor to this insight, focusing on how to measure what people actually experience while working. Their breakthrough, published in 1976 and consolidated in the 1980 book Work Redesign, showed that jobs motivate indirectly by shaping three psychological experiences—meaningfulness, responsibility, and knowledge of results. Autonomy, end-to-end ownership, and feedback were not “soft” factors; they were structural requirements for sustained performance and adaptability.

Fast forward to the AI era, and we face the same dilemma. When AI strives for efficiency, unless we consciously enhance human agency, we will face similar issues. That insight has become newly relevant in the AI era. AI does not eliminate jobs; it automates and accelerates tasks and subtasks. Roles persist, but their scope, skill requirements, and time allocation change as task composition shifts. As AI compresses routine, technical, and analytical work, the hardest-to-automate tasks—judgment, coordination, exception handling, and accountability—become the primary constraints on productivity and outcomes. Human effort and compensation increasingly concentrate on these activities, yet most organizations have not fully internalized this shift.

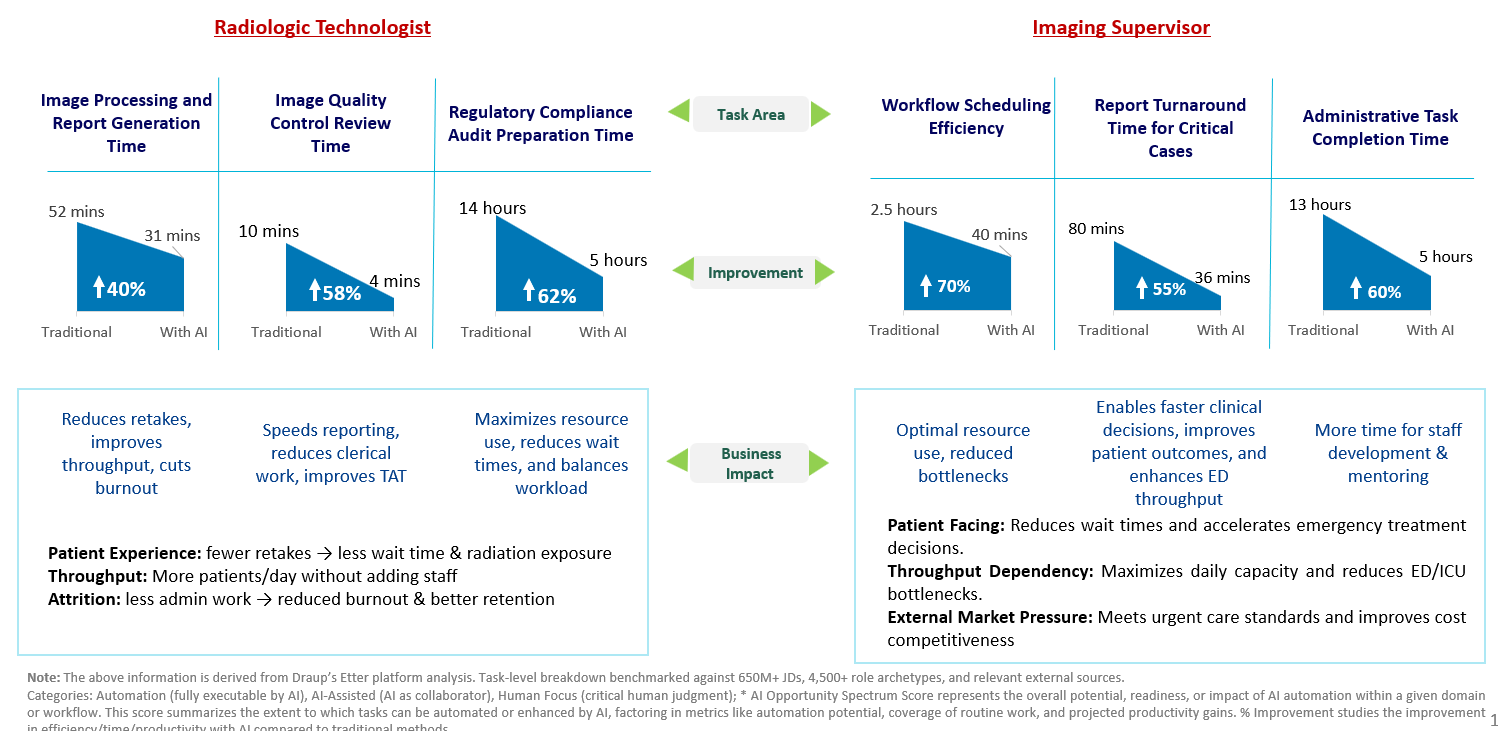

I was recently involved in a hospital work redesign project, which was very rewarding. This example will be very useful for HR leaders (even though it is a hospital setting, the principles are applicable). For each role, we developed simulation snapshots like the ones below

AI reduces time spent on image processing, quality checks, scheduling, and administration, improving throughput and turnaround times. But the real value emerges only when human work is intentionally redesigned around what remains uniquely human.

Radiologists increasingly add value through judgment-heavy tasks such as synthesizing imaging with clinical context, resolving ambiguity and edge cases, prioritizing and escalating critical cases, framing diagnostic narratives, advising clinicians, assessing downstream risk, and owning the consequences of decisions. These tasks restore task significance, autonomy, and accountability—exactly the psychological conditions Hackman and Oldham identified as essential for motivation and performance.

The core lesson is consistent across decades: productivity gains stall not when technology fails, but when work design lags behind technology

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)